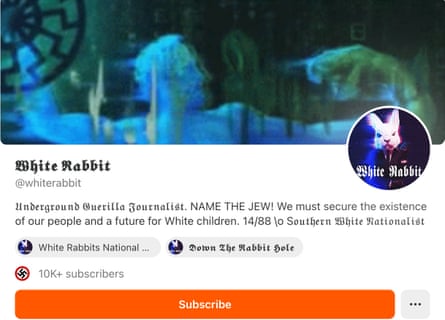

Global publishing platform Substock A Guardian investigation found that it was generating revenue from newsletters promoting extreme Nazi ideology, white supremacy and anti-Semitism.

The platform, which claims to have nearly 50 million users worldwide, allows members of the public to self-publish articles and charge for premium content. Substock takes 10% of the revenue generated by the newsletters. About 5 million people pay for access to newsletters on its platform.

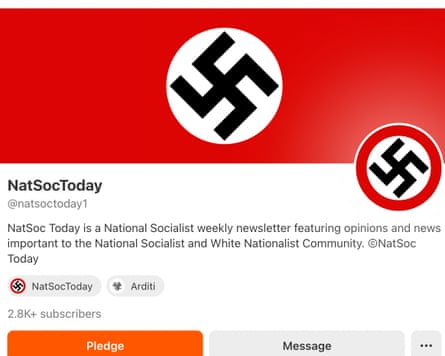

They include newsletters that openly promote racist ideology. One called NatSocToday, which has 2,800 subscribers, charges $80 – about £60 – for an annual subscription, although most of its posts are available for free.

NatSocToday is said to be run by a far-right activist based in the US and its profile picture is the swastika symbol appropriated by the Nazi Party in the 1920s to represent white supremacy. The full name of the Nazi Party was the National Socialist German Workers’ Party.

One of its recent posts suggested that the Jewish race was responsible for World War II and described Adolf Hitler as “one of the greatest men of all time.” Within two hours of subscribing to NatSocToday for the purposes of this research, the substock algorithm sent the Guardian account to 21 other profiles with similar content.

Some of these accounts regularly share and like each other’s posts. Many have thousands of followers.

Erika Drexler, the self-styled “NS [national socialist] activist” with 241 subscribers, shares posts describing Hitler as her hero and “the most qualified leader ever.” The account is US-based and charges $150 for an annual subscription.

Ava Wolff, who has 3,000 subscribers and calls herself an “archivist of articles and videos about history, especially WW2,” appears to be based in the UK. She has a profile that includes swastikas and other Nazi imagery. An annual subscription to her substock costs £38.

Much of the content Wolf posted was related to Holocaust denial. An estimated 6 million Jews died in the Holocaust, but she falsely claimed earlier this month that doctors had found “no one was deliberately murdered by the Germans” and that “death was only from disease and starvation”.

It is unclear whether Drexler and Wolff used their real identities to post their material or whether they wrote under pseudonyms.

Another account, Third Reich Literature Archive, with 2,100 subscribers, shared postcards of a Nazi propaganda rally in Nuremberg in 1938, the year before the start of World War II. It also charges $80 a year for a premium subscription.

The Guardian’s account featured separate posts promoting conspiracy theories about Jewish power and influence and suggested anti-Semitism was a myth.

Algorithm also promoted other extremist content, including newsletters related to the “great replacement” conspiracy theory – suggesting there was a conspiracy to replace white Europeans with people of other races.

Since the start of the Israel-Gaza war in October 2023, there has been a sharp rise in anti-Semitism and Islamophobia. Two people were killed in an attack on a synagogue in Manchester’s Heaton Park on the Jewish holiday of Yom Kippur in October last year. In December, 15 people were shot dead at Sydney’s Bondi Beach celebrating Hanukkah.

Chief Executive of Antisemitism Policy Trust, Danny Stone, said malicious online content often inspired real-life attacks.

As an example, Stone cites the racially motivated killing of 10 African Americans in Buffalo, New York in 2022; A 2018 shooting at a synagogue in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, killed 11 people, and a 2017 attack on a mosque in Finsbury Park, north London, left one dead and several others injured.

“People can and will be inspired by online harm to cause harm in the real world,” he said. “The terrorist who attacked the Heaton Park Synagogue didn’t wake up one morning and decide to kill Jews; he was terrorized.

“The proliferation of algorithmic prompts and malicious content is serious. The Online Safety Act is meant to address illegal content, but says little about legal but so-called harmful content.”

Stone expressed concern about online misinformation about the Holocaust.

“Attending Holocaust memorial events and There is a drop in take-up,” he said. “We know knowledge is already alarmingly low.

“When you have Holocaust denial, inversion or comparisons, you’re seeing the memory of the Holocaust fade away. As we get further away, with fewer survivors, the facts can be lost.

“We must win the battle for that narrative. This online content is doing tremendous damage because if we fail to learn the lessons of that past, we are doomed to repeat it.”

A spokesman for the Holocaust Educational Trust said: “Material like this, which spreads conspiracy theories and Holocaust denial and praises Hitler and the Nazis, is not new but is clearly growing in scope. Substock profits from this hateful material and allows it to be amplified by their algorithm.

“We are well aware that time moves further away from the events of the Holocaust, and eyewitnesses to this history are becoming fewer and fewer. At the same time, anti-Semitism is on the rise – this extremism must be exposed, challenged and eliminated.”

Joni Reid, Labor chair of the All Party Parliamentary Group Against Antisemitism, said she planned to write to Substock and Ofcom to address the Guardian’s findings. Antisemitism is “spreading with impunity” and getting worse, she said.

“We need to take these tech companies into account because this has real-life consequences,” she said. “Jewish people have been complaining about this for years — that this violence online would end up being violence offline, and that’s exactly what happened. We need to start taking this matter more seriously.”

Substock was contacted for comment but did not respond.

Launched in 2017, the platform has previously faced criticism for hosting newsletters that promote extremist views. Its co-founder, Hamish McKenzie, referenced its decision to host Nazi content in his own posts on the site in 2023.

“I want to make it clear that we don’t like Nazis — we just don’t want anyone to hold those views,” he wrote. “But some people have those and other extreme views. Given that, we don’t think censorship (including demonetizing publications) will make the problem go away – in fact, it will worsen it.

“Supporting individual rights and civil liberties, we believe that the best way to eliminate bad ideas from their power is to expose ideas to open discussion. We are committed to protecting and defending freedom of expression, even if it hurts it.”

McKenzie also said the site’s content guidelines “contain narrowly defined prohibitions, including a provision prohibiting incitement to violence.”

If you don’t already have the Guardian app, download it (iOS/Android) and go to menu. Select ‘Secure Messaging’.

“,”displayOnSensitive”: True,”Main text title”:”Secure messaging in the Guardian app”,”Element Id”:”fd170611-d6cd-481e-a8a2-eb65d8341e33″,”Title”:”Contact”,”A closing note”:”

Our guide at theguardian.com/tipsLists several ways to safely contact us and discusses the pros and cons of each.

“,”subtitle”:”Contact us about this article”,”_Type”:”model.dotcomrendering.pageElements.ReporterCalloutBlockElement”,”from active”:1768780800000,”id”:”25ded6f4-6ac7-4d5a-9553-7a9ae417eaf5″,”introduction”:”

The best public interest journalism relies on first-hand accounts from people who know. If you have something to share on this topic, you can contact us confidentially using the following methods:

“,”Safe drop contact”:”You can send messages and documents to the Guardian through us if you can safely use the Tor network without being observed or monitored. SecureDrop Platform.“}}”>