As Kerala heads towards the 2026 Lok Sabha elections, there is a question looming over the state’s political landscape: What does the future of the Left look like after Pinarayi Vijayan?For nearly a decade, Vijayan has been the undisputed face of the Left Democratic Front (LDF), leading it through floods, the pandemic, financial stress and, in 2021, a historic re-election that broke Kerala’s four-decade pattern of successive governments.

But as the prime minister approaches 81, the conversation within party ranks and among voters has quietly shifted from governance to succession.

Congress is in damage control mode after Kerala Chief Minister Mani Shankar Aiyar’s statement

Kerala remains the only state currently ruled by the Left. This makes the 2026 election more than just a routine contest; It is a referendum on the future of communist politics in India, and on whether the LDP can renew itself in time to connect with a new generation of voters.

The Vijayan Factor: Age, Authority, and Continuity

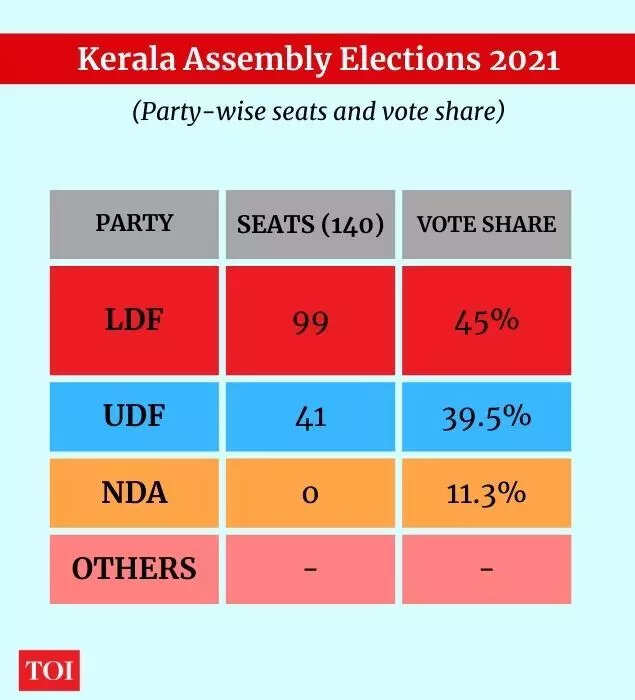

Vijayan, 80, remains the central linchpin of the LDF’s campaign and governance narrative. His leadership was widely praised for the LDF’s victory in 2021, when the front won 99 seats out of 140, marking the first time in four decades that an incumbent president had returned to power in Kerala.Since then, the government has highlighted welfare expansion, including increasing social security pension from Rs 600 to Rs 2,000, infrastructure spending estimated at around Rs 2 lakh crore through budgetary and extra-budgetary resources, and a push towards a “knowledge economy”.

However, the question is less about performance and more about continuity. “Leadership transition is a structural issue for cadre-based parties,” said the Delhi University political science professor. “The strength of the Left has always been collective leadership, but electorally, Kerala voters increasingly respond to recognizable faces.” “If it wasn’t for Vijayan, the Left might not have returned to power,” believes Sherwin, a young independent from Thrissur based in Delhi.

He highlights another important reason why he prefers to vote left: “Because Congress is always fighting among themselves, so I don’t think that’s a good option.”“It’s always the least bad option you vote for, not the best option, and I think that’s the case in politics everywhere now,” he adds.

“Vijayan is not as bright as he may seem,” says Dristi, a member of a left-wing student group. “Maybe now there is no one to replace him, but that does not make him a good choice.”

“I think it is time to give more young faces a chance,” she adds. “Just look at the Politburo, the people sitting there have no connection to the land and the kind of issues that young people face.”

Missing second degree

Unlike previous phases in Kerala politics, no young leader widely expected has been positioned as a natural successor to Vijaya. While several senior ministers and party leaders still enjoy influence within the Communist Party of India (Marxist), the LDP’s senior partner, none of them currently have a state-level mass appeal that can be compared to the Prime Minister.A member of the leftist student wing says that announcing a successor prematurely could lead to tensions between the factions. He added, “The party prefers continuity and teamwork. The focus is on policies, not on personalities.”

But electoral politics has become increasingly personality-driven. The absence of a clear face for the next generation may complicate outreach to first-time voters, especially in urban constituencies where triangular contests are intense, with a growing BJP/NDA footprint.

First-time voters: The changing electorate

The size of young voters has become more evident. According to official figures cited by AIR News after publishing the state’s draft electoral rolls, more than 1,21,000 requests for updates and corrections have been received. Of these, 96,785 were filed to include first-time voters who had turned 18 or sought district changes. For the Lib Dems, engaging Generation Z voters represents both an opportunity and a challenge.

This demographic has grown up in a highly interconnected political environment, shaped as much by social media narratives as by traditional cadre networks.

Increasingly, these first-time voters are becoming the most sought-after political entity on whose side each party wants to influence. “Development and jobs matter to us more than ideology,” said Vishnu, a 22-year-old first-time voter from Alappuzha who studies in Delhi.

We want to see opportunities in the state so that we don’t have to leave Kerala. Another student from Kozhikode pointed out that while welfare measures are important, “the online conversation is different, as people talk about entrepreneurship, startups, and global exposure.”The Community Development Corporation has responded with a renewed focus on digital outreach, alongside its traditional program of home visits, where leaders, from state-level figures to branch secretaries, directly engage families to gather feedback.But Sherwin says: “Although there is a very active young group of people working for the left on the ground, and they are always coming up with different schemes for things, Congress is doing the same thing as well, so I don’t see anything different about what they are doing to attract young people.”

Local Bodies Surveys 2025

If the 2021 Assembly ruling was historic for the FDP, the 2025 local government elections were a reality check.The amount of losses was large. LDF control in grama panchayats decreased from 577 to 340, in group panchayats from 111 to 63, and in district panchayats from 11 to 7.

In urban Kerala, the slide was even sharper: the number of municipal corporations under LDF control fell from five to one, while the number of municipalities fell from 43 to 29.The most symbolic blow came in Thiruvananthapuram, where the BJP captured the establishment for the first time, winning 50 wards out of 101. For the front that has dominated the capital’s civic body since 1980, the loss carried political heft beyond numbers.However, vote share data tells a more accurate story. Despite losing seats, the LDF secured nearly 40% of the statewide votes. The UDF polled 43.21%, retaining the lead but not by an overwhelming margin. The share remained The BJP-led NDA’s lead is about 16%, marginally higher than in previous local assembly polls, and lower than its performance of 19.4% in the 2024 Lok Sabha elections. The party’s gains came from intense seat shifting rather than significant vote expansion.In terms of assembly sector, the United Democratic Front was ahead in 81 constituencies, while the LDF was ahead in 57 constituencies.

However, in 32 constituencies, the LDP’s margin of defeat was between 1,000 and 10,000 votes, suggesting that small fluctuations could reshape the 2026 map.There were also demographic undercurrents. Although minorities make up nearly half of the state’s population, the LDF’s vote share of close to 40% indicates that it retains a significant segment of minority voters among others, even as some sections appear to be uniting behind the UDF in parliamentary contests.

The data point to shifts, but not collapse.From the left’s perspective, local body governance reflects three trends:

- More straightforward three-way contests

- More efficient shifting of seats by the UDF and BJP, and

- Vulnerability is in pockets of the urban middle class, especially among young voters

Whether the 2025 results serve as a precursor to 2026 or a mid-term correction remains an open question.

Between well-being and cognition

The DU professor believes that anti-incumbency alone does not explain the recent setbacks suffered by the Liberal Democratic Front. Instead, “the electoral shifts reflect cross-class dynamics, the consolidation of minority votes behind the United Democratic Front, more nuanced calculations in urban areas, and the targeted expansion of the BJP.”

At the same time, after two successive terms, the FDF appears to be recalibrating its political messaging amid demographic and ideological turmoil.

This recalibration process became visible to the world during the JI controversy. The CPM and the BJP accused the Congress-led United Democratic Front of accepting support from the organisation. The controversy escalated when a senior CPM leader, AK Balan, warned that the UDF government could allow the outfit to influence the Home Ministry and lead to incidents like the 2002-03 Murad riots.

CM Vijayan backed Balan’s statements, though the CPM later termed it his “personal view” after criticism that the speech echoed narratives usually associated with the Sangh Parivar. But the incident was not unusual for the left, which, compared to most of the country’s political scene, avoided entering the arena of sectarian/polarizing discourse. At the same time, the Left has moved to strengthen ties with sections of influential Muslim bodies such as Samastha, including nominating Om Faizi Maqam to the Kerala Waqf Board, a move widely interpreted as a calculated engagement with constituencies seen as different from the IUMF.On the majority side, the government’s role in facilitating the Global Ayyappa Sangamam, linked to the Sabarimala temple run by the Travancore Devaswom Board, has drawn attention given the Left’s earlier strong support for the 2018 Supreme Court ruling allowing entry for women of all ages. On the other hand, as the polls approach and the Sabarimala issue becomes a bigger electoral issue, the Left is increasingly taking an ambiguous position, with its ministers outright refusing to provide any clarification.

Taken together, these events reflect the Lib Dems’ attempt to navigate a more polarized landscape, balancing welfare management and identity-sensitive politics, as it prepares for 2026.

Renaissance playbook

Party leaders recognized the need to “learn from the people” and correct gaps in policy implementation and political communication. A statewide home visiting program has been launched. In parallel, the LDF has intensified its campaign against what it calls financial discrimination by the Centre.

Issue-based mobilization is also being strengthened, including campaigns on MGNREGA allocations and implementation of labor laws.

But the deeper challenge is political positioning. The historical growth of the Left in Kerala was rooted in caste mobilization spanning caste and religion. The recent elections have exposed tensions between welfare-driven governance, secularism, minority concerns, and attempts at socialization more broadly.

A sustainable renaissance may require clarity in ideological messages as much as it requires administrative competence.The question of revival is therefore less a matter of calculation than of adaptability.

What’s next for the left?

For the left, 2026 is not just about retaining power, it is about redefining relevance. The stakes are at the national level: Kerala is the last state under communist rule. The defeat means the absence of a Left-led state government anywhere in India.The immediate strategy appears to be two-fold: strengthening welfare recipients through popular participation, and countering opposition narratives through coordinated political campaigns and social media mobilization.But the structural question remains unresolved: Can the LDF move from a leadership model entrenched in Vijayan power to one that inspires confidence among younger voters?As Kerala’s electorate expands with tens of thousands of first-time voters, the 2026 contest may hinge less on legacy and more on generational trust. Whether the left is able to bridge this gap, organizationally and politically, will determine whether its red stronghold will remain intact or enter a new phase of turmoil.The question now is simple and inevitable: After Vijayan, who?