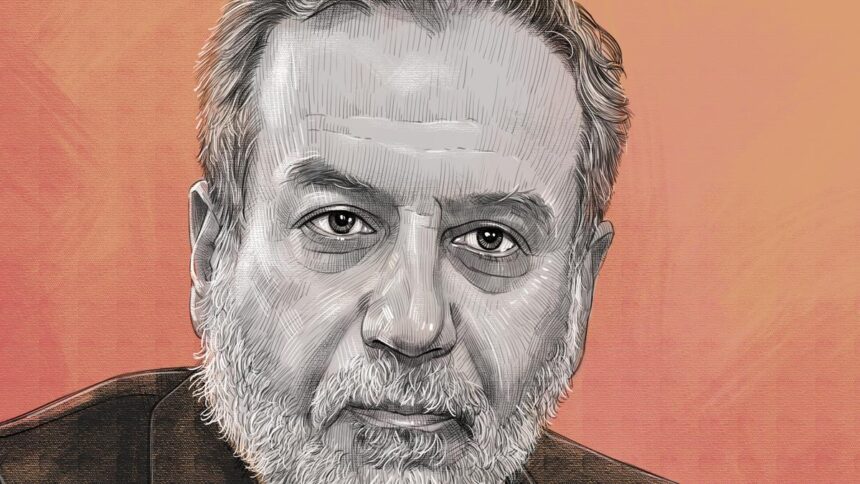

Seyed Abbas Araghchi may have one of the most difficult diplomatic jobs in the world today. His country has experienced its worst internal crisis in four decades. Massive protests and armed unrest broke out In the first week of January, security forces came down violently in various parts of Iran. At least According to official figures, 3,000 people died. The US has sent what President Donald Trump calls a “massive navy” toward Iran. Mr Trump has previously said the US is “locked and loaded” to respond if Iran kills protesters. The US has deployed fighter jets, warships and an aircraft carrier strike group to West Asia. While the risk of military escalation is high, the US has also opened a direct diplomatic channel. “Time is running out For Iran to make a nuclear deal, Mr Trump said on 28 January.

Mr. Aragchi responded kindly. Iran was “ready for a fair and equitable deal”, he said the next day, “but not for coercion”. Iran’s armed forces are “ready with their fingers on the trigger” to respond immediately and forcefully to any attack, he said. This sums up the challenge before him.

Iran is internally tense. It faces the threat of external attacks. It is under heavy Western sanctions and its economy is in serious trouble. All-out war can be catastrophic. But Iran also does not want to show signs of weakness. It does not want to become another Iraq, Libya, Syria or Venezuela. So the task ahead of Mr. Aragchi, with one finger on the trigger, is to find a diplomatic path without jeopardizing vital security interests.

On February 6, he went to the Omani capital, Muscat, for indirect talks with Mr. Trump’s special envoy, Steve Wittkoff, and other officials. There was no progress, but they agreed to meet again. The clouds of war did not lift. But there appears to be a short window for diplomatic engagement to continue, which has reduced the risk of imminent military conflict.

Born Shahs Tehran in 1962, Abbas Araghi overthrew the monarchy during the tumultuous period of the Islamic Revolution and transformed the country into an Islamic republic in 1979. He holds an undergraduate degree from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ School of International Relations and a master’s degree in political science in Islamic political science. Fluent in Persian, Arabic and English, Mr Araghchi did his PhD at the University of Kent under the supervision of Professor David McLellan, an English scholar of Marxism. Mr. Araghi’s essay, ‘The Evolution of the Concept of Political Participation in Twentieth-Century Islamic Political Thought’, argues that modern Islamic political thought has sought to reconcile God’s absolute sovereignty with popular sovereignty.

A reformist promise

Mr. Araghchi rose quickly through the ranks of Iran’s foreign policy establishment. He started as an international relations specialist in the Foreign Ministry in 1988, the year the Iran-Iraq war ended. His first major posting came in 1992 when he was appointed deputy ambassador to the Organization of Islamic Cooperation by President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani. In 1999, when the reformist Mohammad Khatami was president, Mr. Araghchi became Iran’s ambassador to Finland. From 2007-2011, he also served as Iran’s Ambassador to Japan before serving as Foreign Ministry Spokesperson. But the real turning point in his career came in 2013 when he was appointed by President Hassan Rouhani as the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs for Legal and International Affairs.

Mr. Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, a moderate cleric who assumed the presidency after years of chaos Rouhani promised to rewrite Iran’s relations with the world and improve the country’s economic situation. He found a willing partner in US President Barack Obama. Both sides began direct negotiations, which culminated in the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). Under the deal, Iran promised to curtail its nuclear program, which it has always claimed was for civilian purposes, in return for the lifting of international sanctions. The UK, France, Russia, China, Germany and the EU also supported the deal. Mr. Araghchi, then Foreign Minister Javad Zarif’s deputy, acted as chief negotiator in the month-long talks. The nuclear deal was a major breakthrough for the Obama administration and Iran’s rulers. Sanctions were lifted and Iran was allowed to trade freely and invite investments. But in May 2018, President Donald Trump unilaterally withdrew the US from the agreement during his first term. And reimposed sanctions on Iran.

Mr Trump called the JCPOA the “worst deal” in American history. He called it “Maximum Stress ” The policy was adopted with the goal of forcing Iran back to the table. Iran’s moderates felt betrayed. While Mr. Trump tore up the deal, Tehran fully complied with the terms of the deal, according to the IAEA. “We have proven that diplomacy can resolve the most complex disputes. “We have shown that mutual respect and adherence to international law can create progress,” Mr. Araghchi once said of the nuclear deal. “We negotiated in good faith and we faced bad faith,” he said, referring to the U.S. withdrawal from the accord.

As President of Iran Mr. When Rouhani’s successor, Ibrahim Raisi, took office as Iran’s president, Ali Bagheri was appointed as the country’s chief nuclear negotiator. The then Joe Biden-led US and Iran held multiple rounds of indirect talks in Geneva aimed at reviving the nuclear deal, but failed to make any progress. Mr Raisi died in a helicopter crash in May 2024.

12 day war

Masoud Pezheshkian, a physician-turned-politician, won the election on a reformist platform. Mr. Pezheshkian chose Mr. Araghi to head the Foreign Ministry. After Mr Trump began his second term in January 2025, Iran and the US began talks on the country’s nuclear programme. But those talks were undermined by Israel’s bombing of Iran on June 13. The US also joined the war with strikes on Iran’s nuclear facilities, which Mr Trump called a great success. After a 12-day war that ended in a cease-fire, Iran suspended negotiations and suspended cooperation with the IAEA, effectively preventing any international oversight of its nuclear program. But within months, the Iran crisis flared up again, with street protests challenging Iran’s clerical rule and the US and Israel openly backing the protesters.

Even before the Muscat talks began, it was clear that the US and Iran remained far apart even on the nature of the talks. Mr. Araghchi has repeatedly said that the discussions will only focus on Iran’s nuclear program. But the US State Department has said it wants Iran’s ballistic missile program and its support for regional militia groups to be on the agenda. While it remains unclear what exactly was discussed on February 6, the divergence itself underscores the scale of the challenge before Mr Araghchi.

In his PhD thesis, he wrote about reconciling Western democracy with Islamic principles. Now, as Foreign Minister, at a time of grave crisis for his country, Mr. Araghchi has to balance the security concerns of his clerical government and the peak demands of a deeply hostile and militarized America with vital national interests. An extraordinary job indeed.